- Home

- Hannah Moderow

Lily's Mountain

Lily's Mountain Read online

Contents

* * *

Title Page

Contents

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Middle Grade Mania!

About the Author

Connect with HMH on Social Media

Copyright © 2017 by Hannah Moderow

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to [email protected] or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

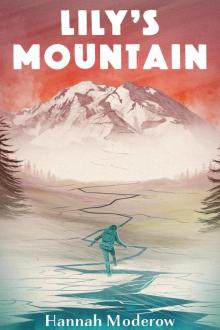

Cover art © 2017 by Matthew Griffin

Cover design by Whitney Leader-Picone

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Names: Moderow, Hannah, author.

Title: Lily’s mountain / written by Hannah Moderow.

Description: Boston ; New York : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, [2017] | Summary: Unable to believe their father died while climbing Mount Denali, twelve-year-old Lily and her older sister, Sophie, climb the mountain in order to rescue him.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016037231 | ISBN 9780544978003 (hardcover)

Subjects: | CYAC: Mountaineering—Fiction. | Fathers and daughters—Fiction. | Sisters—Fiction. | Family life—Alaska—Fiction. | Denali, Mount (Alaska)—Fiction. | Alaska—Fiction.

Classification: LCC PZ7.1.M6368 Lil 2017 | DDC [Fic]—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016037231

eISBN 978-1-328-82903-0

v1.1017

For Mom, Dad, and Andy—with love.

With gratitude to the wise mentors and writing teachers of my life.

Finally, to Erik and Matilda—adventures await!

Dad left three and a half weeks ago with a mug of coffee, a box of chocolate-glazed donuts, and a backpack with everything he needed to climb Denali. Before he left, he pulled me into a bear hug and said, “See you after I touch my toes to the summit.”

“You bet,” I told him, already eager for his return.

As Dad backed out of the driveway, I waved from the porch, wishing more than anything that I could hop into his truck and tag along. Climbing mountains is the surest way to kiss the sky and sleep close to the stars. And Dad always said that from the top of Denali he could taste a little bit of heaven.

Dad touched his toes to the summit, all right. His climbing partner, John, told us he did it on a no-breeze, blue-sky day.

But something happened on the way down.

The phone rang yesterday while I was making Dad’s welcome-home brownies. Sophie and I raced each other through the kitchen to answer it, but Mom beat us there.

“Hello,” she said, her eyes lit up with expectation. Sophie and I stood side by side, watching for Mom’s big smile at the sound of Dad’s voice. But the smile never came. Just weird silence, and then her hands started shaking—hard.

“Are you sure?” she asked, and she took in a really deep breath and held it. She nodded slowly, and when she finally let out her breath, she said, “No, no, no!” Each “no” was louder than the one before. She clicked the phone off and staggered through the back door and onto the porch. She slumped over the railing with her head in her hands.

I chased after her. “What is it? What is it?” I asked as my face got hot and my body started shivering even though it was warm and sunny outside.

Mom lifted her head from her hands and said, “He’s gone.” She paced back and forth along the porch before sitting on the edge of the flower box that Dad had built in time for Mother’s Day this year.

“What do you mean, ‘gone’?” Sophie asked, standing in the doorway.

“He fell in a crevasse, and they can’t find him.”

“Well, they must not be looking hard enough,” I said. It didn’t make sense: Dad knew everything about crevasses, and he knew exactly how to rescue himself if he fell inside one.

“Was he roped up?” I asked.

“No,” said Mom, but Dad always roped up on glaciers.

Mom continued, this time whispering: “They’ve tried everything. He’s gone.”

I shook my head. “No way.”

Mom stood up from the flower box. Her eyes flashed with a panic I’d never seen before. “I told him not to climb that mountain again,” she said. “I had a feeling that something would go wrong.”

No! Denali was Dad’s sacred mountain, and he’d climbed her six times before. Why would he have a problem now?

Sophie ran back into the house and didn’t bother shutting the door. Her feet pounded up the staircase, almost as loud as the pounding in my head at the thought of Dad trapped anywhere.

“Mom, what can we do?” I asked.

She looked across the backyard to nowhere in particular and said one horrible word: “Nothing.” Then she bowed her head like a wounded bird.

“We have to do something,” I said. “I’m not giving up on Dad.”

“Lily, sometimes the mountain wins.”

“No!” I ran into the house and up the stairs. “Sophie, Sophie!” I called.

I found her in Mom and Dad’s closet. She was pulling clothes to the floor just the way she taught me how to make a hide-and-seek spot when I was a little girl. She took Dad’s blue flannel shirt off its hanger, and his gray woolly socks from the drawer, and his tan Carhartt pants that were folded on the shelf. She kept pulling clothes to the floor until the mound was high. Then she lay down and buried her face in the faded fabrics that smelled of Dad and campfires and adventures.

I collapsed too and buried my face in Dad’s favorite blue flannel, but here’s the thing: I knew better than to give up on Dad.

Dad’s been missing in the crevasse for just over two days. Long enough for the phone to ring and ring and ring. Long enough for Dad’s climbing partner, John, to drop off some of his gear. Long enough for Mom to pace the house and for flowers to show up at the door. Long enough for Dad’s outdoor column in the newspaper to show up empty. Well, not quite empty, but they plugged in a filler story about arctic ground squirrel hibernation because Dad wasn’t home to meet his story deadline. And long enough for neighbors and friends to start hovering around.

The first time a knock comes to the door today, I answer it.

“I’m so sorry, honey,” says Barb, Mom’s church friend. She’s holding a green bean casserole with pink polka-dotted oven mitts. Her face is warm and kind, but I can’t take it—those fat tears sliding down her face.

Before I say anything, she walks right into the house. In a blink, Barb and I are in the kitchen alone. I don’t know what to say. I often hike mountains with Dad while Mom’s at church, and how do I respond to those fat tears?

“You know, Lily,” Barb says, “Moses died on a mountain too.”

I’m not sure which is worse: the tears

or the green bean casserole or the thought of Moses dying.

“Dad’s not dead,” I say.

Barb looks at me with owly wide eyes like I’m a crazy person.

“He’ll be back soon,” I finish.

Mom walks in right then, and there’s a silence as tall and icy as Denali. I slowly back out of the kitchen while Barb hugs Mom, and both of them have fat tears sliding down their faces.

Dad always heads for the garage when church ladies come over, so that’s exactly what I do. I walk down the hallway and through the laundry room, and when I get to the garage, it’s quiet and dark—a relief from all the light. It’s almost never dark outside in the summer in Alaska, the land of the midnight sun.

I feel my way beyond the bikes and the ski rack to get to Dad’s workbench. His secret candy stash is on the third shelf from the bottom.

I don’t need light to be able to feel for a small bag of gummy bears. When I find one, I open it with my teeth and start eating.

One bear.

What happened?

Two bears.

How far did he fall?

Three bears.

Why wasn’t he roped up?

Four bears.

I have to find him.

When I was really little, Dad lured me up mountains with gummy bears.

“I’ll give you a red one if you make it to that scraggly spruce tree up there,” he’d say, pointing. I’d think about that red gummy bear all the way to the tree and forget how tired my legs were. Once we reached the tree, Dad would hand over the bear and add a new goal: “I’ll give you a red bear and a green bear if you make it to that rock.” Yes, it was bribery, but it was fun, too. “Hell, if you make it all the way to the top, Lily, you can finish this bag of bears.”

And I would.

I stuff a bunch of gummy bears in my mouth at once, and I hear Dad’s words: “Lily—hope knocks the socks off fear.”

So I eat gummy bears and hope. More gummy bears, more hope.

But I can’t quite push away the smell of green bean casserole and the thought of Moses dying on a mountain.

Dad digs his fingernails into the ice and crawls inch by inch out of the crevasse. When his head comes up into the light above the mountain, he slips and slides back down.

“Help,” I scream, but nothing comes out. “Help!” I scream for real, and my own voice pulls me back into the world. I awake with a jolt from the nightmare.

It’s 12:07 a.m. I blink my eyes open and shut, and then I remember: Dad is missing, Mom served me cold green bean casserole for dinner, and everything is wrong, wrong, wrong.

And the earth is shaking. The brass pulls on my dresser are actually rattling.

Earthquake!

The earth gets going. Really going. Zigging and zagging. The ground rumbles like a train.

I curl my knees up to my chest and clutch the bedpost. From my cocoon I see the framed photograph skid off the nightstand and crash to the floor. Glass shatters.

The earth stops just when I think it never will. Then Mom swings open my bedroom door.

“You okay, Lily?” she asks, her voice weary. She fidgets in the dim light.

“Fine,” I say, and pull the comforter up to my chin, but nothing at all feels fine.

“Do you think Dad felt the quake?” I ask, a sudden vision of ice cracking.

“I don’t know,” Mom says. She stands statue-still in the doorway, like she has a lot to say but can’t bring herself to get started.

“Maybe the glacier shifted in the quake, and Dad can climb out now,” I say.

“I wish,” Mom says. “How I wish.” She lingers in the doorway for another few seconds. Then I hear her slippers pivot and scuffle down the hallway toward Sophie’s room.

Mom must be thinking about Dad in the glacier during the earthquake too.

I sit up in bed. Then I see Dad: down on the floor, beneath the shattered glass. It’s the photo of us standing at the top of Wolverine Peak.

“The best thing in the world is to stand on a mountaintop,” Dad told me when we climbed Wolverine last month—the first big hike of early summer.

We sat at the top of the mountain on the flat ground beyond the jagged boulders. There we sipped our drinks—a can of Orange Crush for me and a mini flask of brandy for Dad. The city of Anchorage glimmered below us: little dot houses, line roads, and patches of brown turning to summery green. Three ravens circled overhead, twirling in the wind.

Most of the city was just waking up, but Dad and I had been climbing for hours. “Never waste the summer sun,” he’d said when he woke me up that day. He had a newspaper deadline that night, but you never would have known it. He lived in the moment when he was in the mountains.

Sophie stayed home that day to get ready for senior prom. High school had officially zapped her love for the mountains. She was more interested in fruity lip gloss, tight blue jeans, parties, and some boy named Clint.

Mom didn’t climb Wolverine with us either. She said she was meeting a friend for coffee, but I think she wanted to keep an eye on Sophie and her prom prep. Mom’s a planner and an organizer. I’m more of a doer . . . just like Dad.

Mom and Sophie missed out. Sitting atop that mountain so early felt like finding the first lucky ladybug of summer.

“There she is,” Dad said and pointed north.

Denali. From our perch on Wolverine, Denali did not look as tall as I knew she was: 20,310 feet. The snowy mountain sparkled under the clear blue sky.

“If I climb back up here when you’re on Denali,” I asked, “could I wave to you over there at the top of the world?”

“I might not be able to see you so far away,” said Dad, “but I’m sure I’d know you were there.” He grinned.

“How?” I asked.

Dad sipped his brandy before answering. “I think of it as mountain sense,” he said. “Those of us who climb mountains know when others are climbing. We connect from the top.”

“Can I climb Denali with you someday?” I asked.

“Yes. We’ll climb her together.”

“Promise?”

“Gummy bear promise,” Dad said. He pulled a bag of bears from his backpack and dumped some of them into my hand. Then he took his own handful.

The promise was delicious—one white bear, four red ones, two yellow, and three green. I could almost taste my two feet on the top of Denali.

As I lie awake, trying to get rid of the earthquake jitters, I think about what Mom said to Dad before he left for the mountain. “Charley, if you keep on climbing Denali, it will kill you eventually . . . and then what?”

At the time, I thought Mom was being dramatic. Dad had been climbing for twenty years, so why would he stop now? What could go wrong now?

“You can’t take the mountains out of me,” Dad said. He assured Mom that this Denali trip would be his last big climb for a while. He had stories to write for the newspaper, he said, and camping trips to go on with all of us.

But I didn’t quite believe him—that his big climbs would slow down. Dad could hardly stand a week without at least climbing Wolverine or another peak in the Chugach Range above Anchorage. Mom loves mountains too, but she doesn’t trust them like Dad does. Doubt creeps in, and Mom can’t push it away.

I’m starting to think Dad crawled out of the crevasse but he’s afraid to come home—afraid that if he does, Mom will never let him climb another big mountain again. Here’s the truth: Dad has to climb mountains, and so do I. It’s what we do, and we’re good at it.

Dad taught me how to hike up mountains before he even taught me the alphabet. I knew tundra underfoot before I knew how to scribble A, B, C on paper. He taught me what to wear to stay warm, and how to scrunch up my toes inside my boots in order to get a good grip on the earth.

Even though Sophie and Mom are in the house tonight, it’s hard not to feel alone. Sophie told me to scram when I knocked on her door and tried to join her in her room.

Sophie’s eigh

teen, six years older than me and ten times more dramatic. When things aren’t to her liking, she stomps around and storms out of the house like a freshly lit sparkler that snaps and crackles all over the place. I can never quite tell her mood, but I like it when the old Sophie shows up occasionally—the sister who loves adventure.

Dad told me that Sophie’s like a ptarmigan in springtime whose feathers are half-white from winter and half-brown for summer. “She’s not sure what season it is,” Dad said. “Don’t worry; she’ll move into her summer feathers soon.”

I hope Dad’s right.

Dad confronted Sophie the night before he left for the mountain. It had something to do with not giving her permission to go to a party. I didn’t hear all of it, but the ordeal ended with Sophie yelling “I hate you,” and she slammed the bedroom door in Dad’s face.

Sophie’s not an I-hate-you sort of girl, but now she’s stuck with those parting words. I. Hate. You. Stuck with them until we find Dad. Then she can have another chance.

The brass handles clink against the bureau. I know what’s coming.

The earth starts shaking—again. An aftershock!

“Stop,” I say, and clutch the bedpost, but everything in my life is shaking, rattling, moving.

When the earth finally stills, Mom’s feet don’t come down the hallway. And there’s no way I can sleep. Not tonight. Dad’s alive, and he might only have a few days left.

I’m his last hope, and I have to come up with a plan.

I pull Dad’s journal out from under my pillow and flip through the pages again. Dad’s climbing partner, John, came by and left it with us yesterday. When he came, none of us asked what we all were wondering: Why hadn’t Dad been roped up when he fell? Had he been reckless? I hoped his journal might answer some questions.

I asked John how he had Dad’s journal. He told me he found it inside the tent pocket. Dad usually wrote his journal entries before bed, snuggled inside his sleeping bag, so he must have forgotten to put it in his pack the next morning.

Lily's Mountain

Lily's Mountain